Allostery is still a badly understood but very general mechanism in the protein world. In principle, an allosteric event occurs when a ligand (small or big) binds to a certain site of a protein and something (activity or function) changes at a different, distant site. A well-known example would be G-protein-coupled receptors that transport such an allosteric signal even across a membrane. But it does not have to be that far apart. As part of the Protein Folding and Dynamics series, I have recently watched a talk by Peter Hamm (Zurich) who presented work on an allosteric system that I thought was very interesting because it was small and most importantly, controllable.

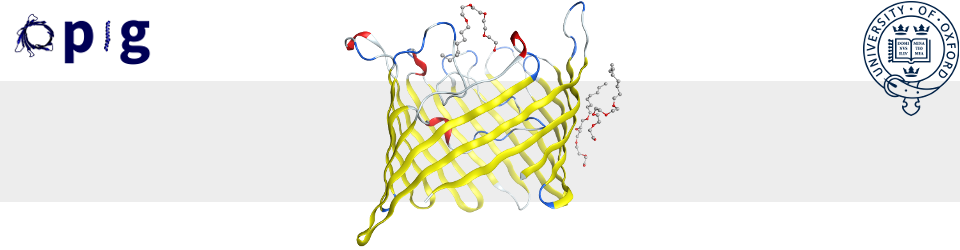

PDZ domains are peptide-binding domains, often part of multi-domain proteins. For the work presented the researchers used the PDZ3 domain which is a bit special and has an additional (third) C-terminal α-helix (α3-helix) which is packing to the other side of the binding pocket. Previous work (Petit et al. 2009) had shown that removal of the α3-helix had changed ligand affinity but not PDZ structure, major changes were of an entropic nature instead. Peter Hamm’s group linked an azobenzene-derived photoswitch to that α3-helix; in its cis configuration stabilizing the α3-helix and destabilising in trans (see Figure 1).